A cloud of smoke and ash trailed behind us, swallowing the road as we moved on down the highway to the next annihilated town.

…this pure-hearted child shining in the midst of all the black and grey.

As we drove through the neighboring towns that had burned, I noticed a little girl standing outside her home, waving at the fire crews passing by. It felt surreal—this pure-hearted child shining in the midst of all the black and grey. The contrast was eerily beautiful. She reminded me of a wildflower pushing through cracked cement, a quiet resilience that, to this day, still makes me choke up.

Because her resilience felt familiar. It was the same working-class resilience I knew—one that pushes through, no matter how dark things get. One that refuses to be swallowed by destruction. One that always, somehow, reaches for the sun again.

The surrounding towns had been decimated by the second-largest wildfire in California history. But outside a small Mexican restaurant in Chester, people gathered—eating, drinking, and maybe just trying to bond over the trauma they had endured. The smell of smoke rolled back in at dusk as we stood, watching from the adjacent parking lot, preparing for our overnight shift to monitor the highway and prevent any new fire starts.

Chester is a working-class town built on tourism, timber, and the surrounding forest, and ultimately survived the Dixie Fire. We had traveled up from Los Angeles, assigned to a strike team based out of Susanville. This was my first time witnessing devastation like this—entire towns reduced to piles of ash and charred cement blocks. Here and there, a lone business had survived, but most of what I saw was simply gone.

Here was a restaurant full of people who had lived through devastation, just trying to find a bit of peace.

I made my way to the restaurant under the guise of needing the restroom, to which my captain simply replied, "Hurry up." Walking in, I asked if I could use the restroom. The noise of conversation and laughter instantly hit me—it was a stark contrast to the destruction we had just witnessed. People were smiling, talking, and trying to find some normalcy amid the chaos. It was one of those moments where the old saying, "I’ve gotta laugh to keep from crying," really hit home.

Here was a restaurant full of people who had lived through devastation, just trying to find a bit of peace.

As I walked in, I felt the weight of eyes on me. I was wearing my yellow long-sleeve wildland firefighter shirt, which I wouldn't have worn unless we were on the clock—mainly to avoid being teased or called a hero jokingly by my crew.

When I finished, I walked out to see my captain and our engineer ordering food, which I did as well. After being told it would be about five minutes for our food, we waited outside.

A cloud of smoke and ash trailed behind us, swallowing the road as we moved on down the highway to the next annihilated town.

“How long do you think y’all will keep doing this? Hard work, I’m guessing—tough on the body,” one of the residents asked us as we waited for our food. He had just thanked us for helping fight the fire, and we hesitantly muttered, “Thank you” in response. Not because we weren’t grateful, but because it felt wrong—shaking this man’s hand while so many others were still out there, still working.

Any first responder who didn’t feel at least a little guilty accepting praise, to me, was someone who wanted it. We called them “t-shirt firefighters”—the ones who did the job for the title, for the shirt they could wear around town, to flirt, to say, "Look at me, I’m better than you." They weren’t in it for the love of the job, for the people, or to help. It was for selfish reasons.

“Yes, sir. I’ve been doing it for a while now, and I guess I’ll keep going until my body tells me otherwise,” Zim replied with his signature smile—the kind that made his forehead scrunch up and the crow’s feet around his eyes stand out. Not as a sign of age, but of a life spent working hard, leading, and building something long before fire—he was a plumber’s son, after all.

“Yeah, I was a volunteer before this. I like it,” Cammucio added.

I was the last to answer. “Yeah. I guess I’ll do it until I can’t anymore. I love it. I love helping people, the challenge of the work, being out in nature, in places no one’s seen in a long time. This is the best job I’ve ever had.”

Zim slowly nodded in agreement. I hadn’t worked with him much since he was on the other crew, but after this fire, it felt like our friendship was cemented. “I’d have to agree, Mr. Robo,” he said with a grin.

The resident shook all of our hands once more before heading off, and not long after, we did the same—grabbing our food and piling into the truck. As we drove away, the vibrant Mexican restaurant, filled with laughter, tears, and uncertainty, faded into the distance. In its place, a cloud of smoke and ash trailed behind us, swallowing the road as we moved on down the highway to the next annihilated town.

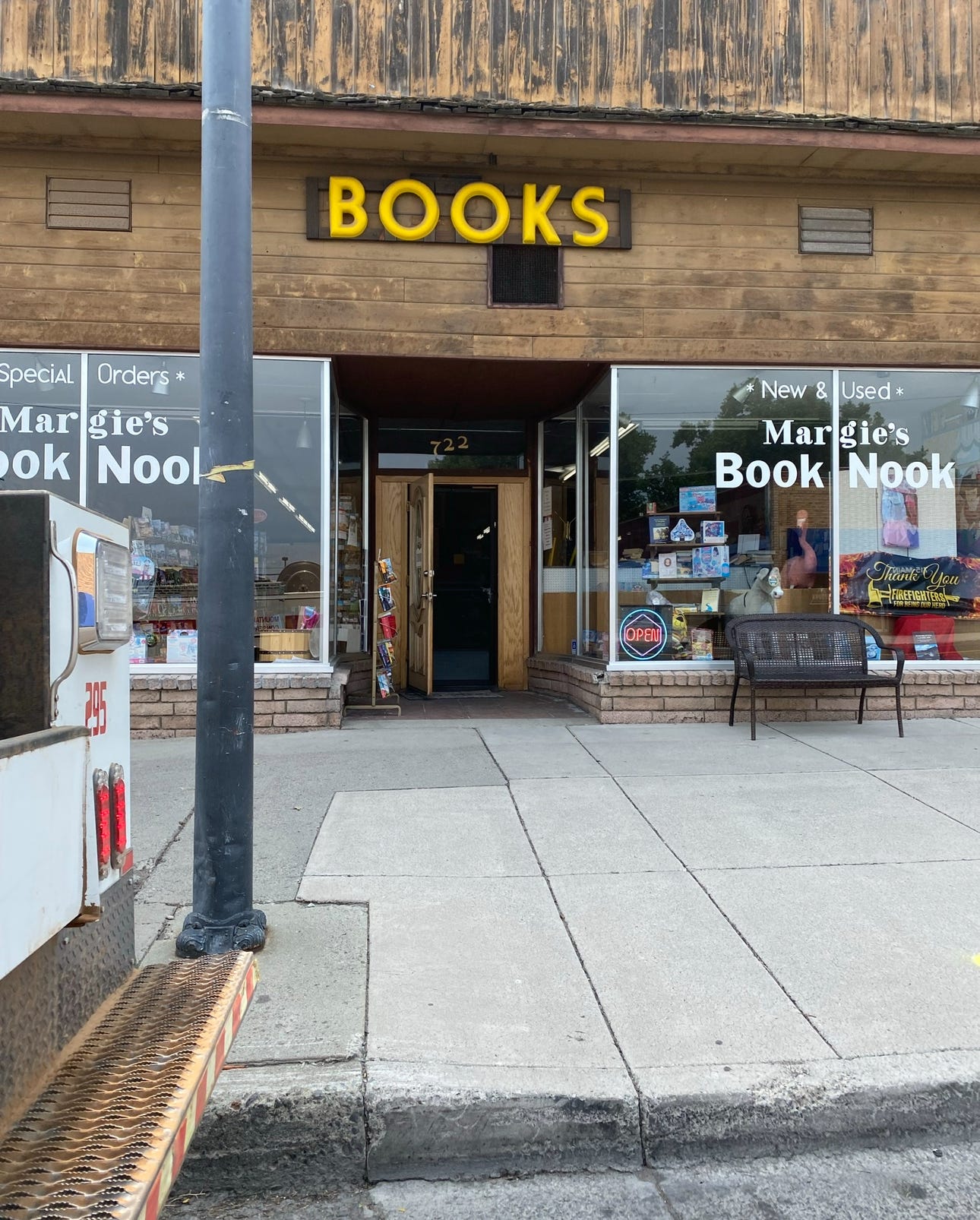

The bookstore in Susanville was a mess, and I loved it. After a week on the fire, we finally got a day off to explore. Some of the guys headed to the gun store or the pawnshop—"Ammo prices are better up here," one of them would later tell me—but I made my way to the bookstore, tucked near the edge of town.

Just as I was about to check out, I got a text from a guy on the strike team: one of the restaurants in town was giving away free Hawaiian BBQ. We were starving for it. A few days earlier, Guy Fieri had rolled up to the Dixie Fire base camp in Susanville with his big BBQ truck—only to serve us pasta. To this day, I’m still pissed about that.

Restaurants handed out food, small-town gyms let us work out for free, and local businesses found ways to help. The bookstore knocked 50 percent off my total. I told them it wasn’t necessary, but they insisted. There was no fanfare, no social media posts, no one angling for clout. Just working-class people—many who had lost something in the fire or knew someone who had lost everything—giving what they could, simply because they could.

You don’t find that kind of genuine kindness in wealthier places. There, generosity comes with a tax write-off or some emotional or financial return. But here, in a town that had already lost so much, people still gave. And that’s the kind of thing you don’t forget.

The generosity of working-class people, to others like them, living paycheck to paycheck, fire to fire, season to season, to give all you can to help when you can barely help yourself.

A waiter serving food, a wildland firefighter dragging hose, a small bookstore clerk giving out discounts when they probably shouldn’t, a little girl waving to fire trucks as they pass to show that the world hadn’t truly ended.

The kindness of those who feel like strangers, but in reality, are reflections of the same fight we all share in the American working class.

-Robo

Share this post